Paper Template

COUNSELLING IN INSTITUTIONS OF HIGHER EDUCATION: CHALLENGES AND

SUCCESSFUL STRATEGIES

Synthia Mary Mathew1 and Alice Eliza Sherina, C. 2

ABSTRACT

Education aims at whole person development and unless the higher education institutions view the student as a whole person this objective cannot be achieved. Successful academic learning implies growth and development of the whole person. Counselling services have to be regarded as an indispensable part of every institution of higher education to appropriate this holistic view of the person and the process. But, even in institutions where such services are available the numbers of students who avail these remain minimal. Individuals who experience psychological and interpersonal concerns rarely pursue counselling or other mental health services either due to ignorance or social stigma. The restrictive nature of social stigma in seeking help is more evident in approaching such services offered at institutions of higher education. Here the very nature of the context, that is, the confines of the campus, threatens the already fragile sense of self of the adolescent who needs help. To address this concern, this paper aims at presenting a few successful strategies for making counselling in Higher Educational Institutions more meaningful for a larger group. The paper identifies the role of peer group training and group sessions for students, namely IPR (Inter - Personal Relationship) sessions in helping students to overcome the stigma. A detailed discussion with empirical evidence is provided regarding the implementation of these strategies at the Counselling Unit at Lady Doak College, Madurai.

Key words: Counselling in Colleges, Stigma, Peer counselling, Mentoring, IPR Sessions

Introduction

The individual at different stages of life goes through diverse challenges. Unless properly equipped, these challenges can become overwhelming barriers causing developmental impediments and hindering the person from actualising one's true potential. Of the various stages of life ranging from infancy to older adulthood, adolescence requires the highest amount of preparation as it demands the greatest psychological, social and cultural changes. These challenges get aggravated due to the alterations in the intellectual and academic demands on the late adolescent as they enter the portals of an institution for higher education.

Higher education is one of the most valued experiences and for many students college marks the beginning of increased independence, of decision making and of managing shifting roles (Hinkelman & Luzzo, 2007). The student of higher education is at a critical stage of development, because they are actively exploring their identities and attempting to define themselves (Jourdan, 2006). Therefore the knowledge of how an adolescent grows, learns and evolves and the provision of the required support systems, is absolutely necessary to bring about the desired outcome of the learning process in an institution for higher education.

Need for Counselling Higher Education

Present day adolescents are plagued by various stressful demands. Along with their academic and intellectual pursuits students in Colleges and Universities must adapt to environments characterised by rapid change, ambiguity, uncertainty and depleted support systems. They must also cope with a myriad of personal and psychological problems that range from basic adjustment issues related to development, learning and career concerns to clinically diagnosable mental illness.

According to Arthur Chickering there are seven specific developmental tasks a college student should acquire before completing the college education. They are; competence, autonomy, managing emotions, identity, purpose, integrity and relationships. These tasks get expressed in the three key issues of young adulthood, namely, career development, relationships and formulation of an adult philosophy of life. College counselling services should be planned and provided around these key issues (Chickering & Reisser,1993). The need for college counselling services gather significance in this context, where the mission of colleges and universities is not just to produce skilled degree holders capable of making a living but wholesome persons who can manage and cope with all the storms that living demands.

In India, which holds the third position in the world in higher education next to US and China, which expands at a very fast pace the need for counselling services are all the more mandatory. With 700 universities and more than 35,000 affiliated colleges enrolling more than 20 million students, Indian higher education is a large and complex system. As of 2013 our country has 44 central universities, 306 state universities, 129 deemed universities, 154 private universities, 67 institutions of national importance and 35539 colleges both government and private (Choudaha,2013). The multi-cultural, multi-lingual and multi-religious nature of the Indian subcontinent makes the needs of the student population much more diverse and complex and emphasises the need for a perfect support system to help these students handle the challenges of the current stage of their life.

Counselling services in higher education, contributes to student's development, adjustment and learning at the same time preventing dangerous and self-defeating behaviour. This enables the individual to meaningfully develop and actualise as a person. The mechanisms that colleges and universities utilise to achieve this goal vary dramatically from one institution to another depending heavily on the philosophy, mission, available resources and the particular needs of the institution (Gilchrist, 2015).

Counselling Services at Lady Doak College

Lady Doak College, an Autonomous Institution Affiliated to Madurai Kamaraj University, had its inception in 1948 and it offers liberal arts education to women students in south Tamilnadu. Being located at Madurai, the college caters to the academic needs of a semi-urban population. As it is committed to the overall wellbeing of the person, counselling services were a part of its provisions from early 1980's taking umpteen initiatives to make this service accessible to every student.

Strategies at Lady Doak College

The Counselling Unit at the college offers training to selected faculty members in Basic Counselling Skills and students in Peer counselling. During the earlier years the services were provided through these staff members and the Peer counsellors. As the institution grew in quality and quantity the need for a professionally trained counsellor on campus was felt and later the services were mostly provided through the professional counsellor with the support of the unit members and the Peer counsellors.

One of the most significant challenges faced by the institution was the difficulty in making counselling services accessible to all who needed help. This challenge emerged from the lack of awareness among a majority of students about the services provided and also the stigma associated with help seeking behaviour. Different strategies were evolved over the past 10 -15 years to meet this challenge and some have been successful in meeting the objective of the counselling unit.

Orienting the newcomer

At Lady Doak College, information regarding the counselling services was given to the freshers during the I Year Orientation program for both undergraduates and postgraduates, which is held on the first day of their college studies. A detailed information regarding the place, person, time and availability helped the students in using the services as and when required.

'Orientation' is defined as the deliberate programmatic and service efforts designed to facilitate the transition of new students to the institution; to prepare them for the institution's educational opportunities and responsibilities, to initiate the integration of new students into the intellectual, cultural, and social climate of the institution and support the family members of the new student (NODA, 2012). Components of a successful orientation program assist students in gaining the attitudes, knowledge, skills and opportunities that will assist them in making a smooth transition to university or college community, thereby allowing them to become engaged and productive community members (Hibel, 2015).

Peer Counselling

Peer counselling is an effective way of reaching students beyond the traditional college counselling centre. Generally needy students turn first to friends for help, then to close relatives before finally turning to faculty and counselling services (Gladding, 2009).

In agreement with this, during the initial years of the counselling unit few faculty members were send for special training in Peer Counselling and Pre- helping Skills. They gave training in Peer counselling to selected students from each department. The students were expected to act as a link between the larger student body and the members of the unit. Frequent feed-back sessions after the training helped them in getting the right direction and bringing those who required help to the Counselling unit.

Research has indicated that peer counselling can be as effective as professional counselling and Peer counsellors unlike professional counsel lors are available to help their peers anytime and their counselling sessions are informal discussions and conversations which are not threatening. That is why some institutions have placed it at the heart of their proactive counselling programs. (Odirile, 2012)

Mentoring

During the last decade, though the professional counsellor addressed varied issues, difficulties related to heterosexual relationships was identified as a recurring problem among many students. The development in communication technology added intensity and complexity to the above mentioned problem and the need for a better strategy to prevent rather than intervene was strongly felt. As a response to this, a program on "Healthy transition from adolescence to adulthood" was developed to help the First year UG students on issues related to, relationships, reproductive health and sexuality. Selected faculty members were given training in conducting this program. To conduct a program like this in a meaningful manner, faculty need to take the role of mentors, hence, special training programs on mentoring were given to the same group of faculty. This provided a lot of time and freedom for the students to openly share and clarify issues that were disturbing them and thereby gain an added accessibility to the services of the counselling unit. A recent survey revealed that 78% of students want the program to be continued.

Mentoring in higher education is rooted in those informal advisory relationships that develop between faculty and graduate students, serving a socializing role for students (McWilliams &Beam, 2013). Research studies also indicate that mentoring by college faculty has a positive impact on students' persistence and academic achievement in college (Crisp and Cruz 2009) and helps prepare them to be successful in careers (Schlosser, Knox, Moskovitz, and Hill 2003). Mentoring relationships can involve the provision of career, social, and emotional support in a safe setting for self-exploration that results in positive academic and personal outcomes for students (Johnson 2006).

Interpersonal Relationship Sessions

The adjustment difficulties of college students have been an ongoing issue across the globe. Many studies have proved that the adjustment difficulties like appetite disturbance, concentration problems and depression are most evident in freshmen (Lee, et al,2009). Freshers at college go through additional problems of adjustment along with the natural challenges of evolving an identity and understanding new situations. Freshmen are more likely to experience loneliness, low self esteem and higher frequencies of life changes than their seniors (Beck, et al., 2003)

To help the freshers at Lady Doak College tide over similar difficulties in adjusting to a new academic environment, the counselling unit organised group sessions with the counsellor. During these sessions the students were encouraged to share their feelings and the related experiences. The sessions along with self disclosure also provided an opportunity to understand and strengthen interpersonal relationships and thereby were termed as Inter Personal Relationship (IPR) sessions. Interpersonal relationship programs enable participants to maintain balance between their cognition, emotion and behaviour. Systematic functioning of these processes help students to interact with other people and improve interpersonal relationships (Kim & Park, 2010).

The IPR sessions held at the Counselling Unit at Lady Doak College helped the participants in experiencing an emotional comfort, stronger relationships and also gave them confidence to approach the counsellor personally for their needs. Research also shows that, the feeling of being understood, valued, and supported by other people helps establish and maintain satisfactory relationships (Canevello & Crocker, 2010). It is thought that the responsive relationship built among group members while responding to and supporting each other's thoughts and feelings was a key contributing factor to good interpersonal relationships (Yoon, Hee Sang1 ·Kim, Gyung-Hee2 ·Kim, Jiyoung, 2011).

Empirical Assessments

The services of the counselling unit at Lady Doak College, became more accessible to the student body through strategies that were implemented at different periods of time. At present the strategies that are used for making the services accessible to students are; the awareness provided through Orientation Program, referrals through Faculty Mentors and the Group IPR sessions.

A. A Survey

To gain a better understanding of the challenges faced by the counselling unit at present and effectiveness of these strategies a survey was undertaken among a conveniently selected sample of 60 First year Under Graduate Resident students at Lady Doak College.

The objectives of this survey were to find out the respondent's:

- Awareness of the counselling services provided at college

- Perception of stigma associated with help seeking behaviour.

- Response towards the IPR (Inter Personal Relationship) sessions.

A questionnaire which contained items related to awareness, perceived stigma and response to IPR sessions were distributed to a sample of 60 resident students representing the different residential halls. A descriptive analysis of the collected data revealed the following:

Table. A.1. Distribution of respondents with regard to awareness of the counselling services at college and the means through which the awareness was gathered:

| Means of Awareness | N | Percentage |

| Orientation program | 19 | 32% |

| Group sessions with the counsellor |

16 | 27% |

| College handboo | 7 | 11% |

| Students | 6 | 10% |

| Teachers | 2 | 3% |

| Not aware | 10 | 17% |

| Total | 60 | 100 |

While 83% of the respondents were aware of the counselling services at college, of which 38% gained the information through the college orientation program and 27% through group sessions with the counsellor, 17% of the respondents were not aware of the provision at the college.

Table. A. 2. Distribution of respondents with regard to ways of handling a personal problem during the last one year in residence

| Experience of problems and ways of handling | N | Percentage |

| Handled the problem oneself | 10 | 40% |

| Shared with a friend | 9 | 36% |

| Shared with a Family member | 4 | 16% |

| Shared with a Teacher or Warden | 1 | 4% |

| Shared with the college Counsellor | 1 | 4% |

| Total | 25 | 100% |

Those who experienced problems during the last one year (n-25) engaged in different ways of coping; among the 60% share with another person, whereas 40% of the respondents handle it by themselves either by thinking or by distract themselves from the problem by doing other activities.

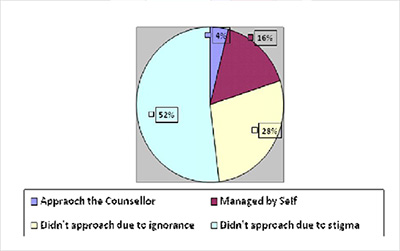

Figure. A. 1. Distribution of respondents with regard to approaching the counsellor while experiencing a problem

Among those who experienced problems

during their first year (n=25), only 1 person (4%)

approached the counsellor for help, 16% felt they

could manage by themselves, 28% did not know

how to seek for help and a majority of 52% did not

approach the counsellor for help due to stigma arising

from fear of labelling either by self or others.

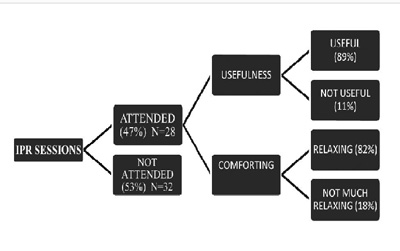

Figure. A. 2. Distribution of respondents with

regard to attending and benefiting from the

IPR sessions

Among the 60 respondents, 47% (n=28) have attended the IPR sessions with the counsellor out of which 82% (n=23) felt relaxed after the session and 89% (n=25) considered the sessions and the counselling services having future benefits.

These findings reiterate the success of some of the strategies mentioned earlier, namely information given during the Orientation Program and the role of IPR sessions. Both these seem to have made the counselling services at college more accessible to students. Still many students appear to be ignorant about the available services and are having a stigma in receiving the same.

B. Analysis of Secondary data

In addition to the above mentioned survey an analysis of secondary data, available in the Counselling Unit as case entries ('03-'06 & '13-'15), was also made with the following objectives:

- To find out the ratio of students who accessed the counselling services for individual therapeutic counselling.

- The role of the various strategies over the years in bringing students for counselling, namely, referred by Staff members, referred by Peercounsellors, after IPR sessions

The number of students who accessed the service and the manner in which the services was made available to them was identified and the values are presented below:

Table.B.1. Year wise data (2003-'06 &'13-'15) regarding the ratio of students who approached the professional counsellor for help.

| Academic year | Overall student strength (App.) | Students who accessed counselling Services | |

| N | % | ||

| 2003 -04 | 3500 | 12 | (0.343%) |

| 2004 -05 | 3550 | 12 | (0.341%) |

| 2005 - 06 | 3600 | 10 | (0.278%) |

| 2013 - 14 | 4000 | 119 | (2.98%) |

| 2014 -15 | 4200 | 104 | (2.48%) |

The number of students who received help in the years 2003-'06 is observed to be a negligible minority. It is understood that once the functioning of the unit changed from the informal help provided by the unit members during its initial years (80's through 90's) to a more or less formalised help given by the part time professional counsellor (early 2000's), who was available on campus for two days a week, there was a gradual reduction in students who availed the help. Though a part-time professional counsellor was available on campus from early 2000's the takers appear to be few. In comparison with the data pertaining to 2003-'06, the data regarding 2013-'15 shows an increase in the number of students who availed the help from the professional counsellor, who was still available for just 3 days a week.

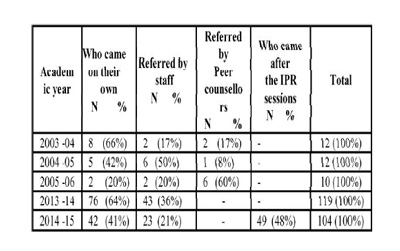

Table B. 2. Year wise data (2003-'06 &'13-'15) regarding the number of students who approached the professional counsellor and the strategy which was effective in bringing them

In the years '03-'06 none of the strategies seem to have been effective enough in making the services accessible to a large number of students. Though training in Peer Counselling and its follow up was a successful practice existing from the late 80's for more than two decades and could bring needy students to the unit for help during these years, the number of students who benefitted through this strategy appeared minimal in the early years of 2000's. A gradual decrease in the effectiveness of Peer Counselling as a strategy to reach out to students was felt during these years as there was an increase in the number of students and related changes in the functioning of the college.

This led to a need to chart out other courses of action and group IPR sessions for freshers were one such strategy. The data for 14-15 reveals the role played by the group IPR sessions in making the services more accessible to students. In the year '13-'14 though IPR sessions were conducted the number of students who came for help due to it could not be ascertained. It is possible that among the 64% who came on their own a few would have come after attending the IPR sessions.

It is interesting to note that in both these tabulated data pertaining to the years 2003-'06 and 2013-'15, there's a reasonable number of students who accessed the service of the counsellor as referred by a staff member. Though fluctuating, a considerable number of students availed the services of the counsellor due to the involvement of faculty mentors. This emphasises the role played by mentoring and the 'Healthy transition program' in creating awareness among the faculty about the student problems and the need for counselling. This also indicates the involvement on the side of the faculty in making these services more accessible to the needy students.

Conclusion

This paper highlights the need for formalised Psychological counselling services in Institutions of higher education, the challenges faced in providing these services and the strategies which could be implemented.

On the basis of the assessments it could be concluded that though there is an increase in the ratio of students who access counselling services, stigma is still an issue to be reckoned with. Strategies need to be planned and implemented according to the demands of the time as effectiveness of the strategies in making the services accessible to students vary at different periods of time. When Faculty members are given a significant and specific role to play, they get more involved in making the services accessible to a larger group of students.

To wrap up, we would like to reiterate that, effective provision of the counselling services in higher education is possible only when strategies are planned and executed by meaningfully integrating it with the socio-cultural context, the emotional climate the ethos, the vision and mission of the institution.

References:

- Gladding, S.T. (2009). Counselling A comprehensive Profession. New Delhi: Dorling Kindersley.

- Johnson, W.B. (2006). On Being a Mentor: A Guide for Higher Education Faculty. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Beck, R., Taylor,C., & Robbins. M. (2003). Missing home: Sociotropy and autonomy and their relationship to psychological distress and homesickness in college freshmen. Anxiety, stress and coping, 16, (2), 155-66. Retrieved from http:// www.acu.edu/academics/cas/psychology/ documents/beck/Missing%20Home.pdf

- Canvello. A., & Crocker. J. (2010). Creating good relationships: Responsiveness, relationship quality and interpersonal goals. Jouranl of Personality and Social Psychology, 99,78- 106. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi. nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2891543/

- Choudaha. R. Statistics on Higher education . Retrieved from h t t p : / / www.dreducation.com/2013/08/data-statistics- india-student-college.html

- Crisp, G., & Cruz. I. (2009). Mentoring College Students: A Critical Review of the Literature between 1990 and 2007. Research in Higher Education, 50, 525-545. Retrieved from http://link.springer.com/article/ 10.1007%2Fs11162-009-9130-2

- Gilchrist, L.Z. (2015). Personal and Psychological counselling at colleges and Universities-Psychotherapy academics and learning, career counselling, Educational and Psychological outreach. Education Encyclopedia- State University.com. Retrieved from http:// education.stateuniversity.com/pages/2317/ Personal-Psychological-Counseling-At- Colleges-Universities.html

- Hibel, A. (2015) New student programs a look inside orientation, transition and retention programs. Article provided by Higher EdJobs. Retrieved from h t t p : / / w w w. a ca demi c3 60 . com/a r ti c le s / a r t i cl e Display.cfm?ID=402

- Hinkelman, J.M., & Luzzo, D. A. (2007). Mental Health and Carrer development of College students. Journal of Counselling and Development, 85, 143-147. Retrieved from http://www.niu.edu/stuaff/grad_resources/ GAJobDescriptions/hinkelman_cd.pdf

- Jourdan. A. (2006). The impact of the family environment on the ethnic identity development of multi-ethnic college students. Journal of Counselling and Development, 84, 328-340. Retrieved from http://onlinelibrary. wiley. com/doi/10.1002/j.1556-6678.2006.tb0 0412.x/abstract

- Kim, S. H., & Park, G. H. (2010). The development of interpersonal relationship harmony program for university students. The Korean Journal of Counselling, 11, 375-393

- Lee, D., Olson, E. A., Locke, B., Testa, M. S., & Eleonara, O. (2009). The effects of college counselling services on academic performances and retention. Journal of College Student Development, 50 (3), 305-19.Retrieved from https://muse.jhu.edu/ login?auth=0&type=summary&url=/journals/ journal_of_college_stud ent_develop ment/v050/50.3.lee.pdf

- McWiliams. A. E.,& Beam, L.R. (2013)Advising, Counseling, Coaching, Mentoring: Models of Developmental Relationships in Higher Education . The Mentor an Academic advising journal. (June 28, 2013) . Retrieved from http://dus.psu.edu/mentor/2013/06/ advising-counseling-coaching-mentoring/

- Odirile. L. (2012).The role of peer counselling in a university setting: the University of Botswana. Proceedings of the 2012 Summit of the African Educational Research Network, 18-20th May. Retrieved from http://www.ncsu.edu/aern/TAS12.1/ AERN2012Summit_Odirile.pdf

- Schlosser, L.Z., Knox, S., Moskovitz, A.R., & Hill, C.E. (2003). A Qualitative Examination of Graduate Advising Relationships: The Advisee Perspective. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 50, 178-188. Retrieved from http://psycnet.apa.org/psycinfo/ 2003-03644-007

- Yoon, H.S., Kim, G.H.,& Kim. J. Effectiveness of an interpersonal relationship program on interpersonal relationships, self esteem and Depression in nursing students. Journal of Korean Acaedemy of Nursing, 41(6),805- 813. Retrieved from http:// www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22310865

- Annual report 2012-1pdf, National Orientation Directors Association. www.nodaweb.org